From Correlation to Causation in Machine Learning: Why and How our AI needs to understand causality

What’s wrong with correlation?

In May 2016, the COMPAS algorithm was flagged as being racially biased [1]. This algorithm was used by the US to guide criminal sentencing by predicting likelihood of reoffending. It estimated a black person was more likely to re-offend than a white person with the same other background factors.

The problem was, the algorithm was mistaking correlation (patterns of crime in the past) with causation (that being black makes you more likely to commit a crime).

This can be a problem in medicine as well. Consider the following:

100 patients are admitted to hospital with pneumonia, of which 15 also have asthma. The doctors know asthma puts them at higher risk of getting more sick, so give them a more aggressive treatment. Because of this, the patients with asthma actually recover more quickly.

If we use this data to train a model, and aren’t careful, the model may conclude that asthma actually improves recovery. As a result, it may recommend treating less aggressively. Of course, we can see this is wrong – but to an AI model it’s not so obvious.

From statistics to machine learning

This problem of correlation without causation is an important issue in machine learning.

As the ryx,r blog points out, a key distinction between statistics and machine learning is where we focus our attention. In statistics, the focus is the parameters in the model. E.g. for a model that predict house price, we want to understand each parameter and how it impacts the prediction.

In machine learning, on the other hand, the focus is less about parameters and more about predictions. The parameters themselves are only as important as their ability to predict an outcome of interest.

Machine learning is really great at identifying complex, nuanced relationships within large volumes of data to predict outcomes with high accuracy. The issue is: these relationships are correlations, not causations.

What’s the difference between correlation and causation?

In short:

correlation−confounders=correlationA correlation is an association. When one thing goes up, another goes down. Or up. It doesn’t really matter, as long as they change together.

But we don’t know whether the first change caused the second change. Or even if the second cause the first. There could also be a third factor, which actually changes both points independently.

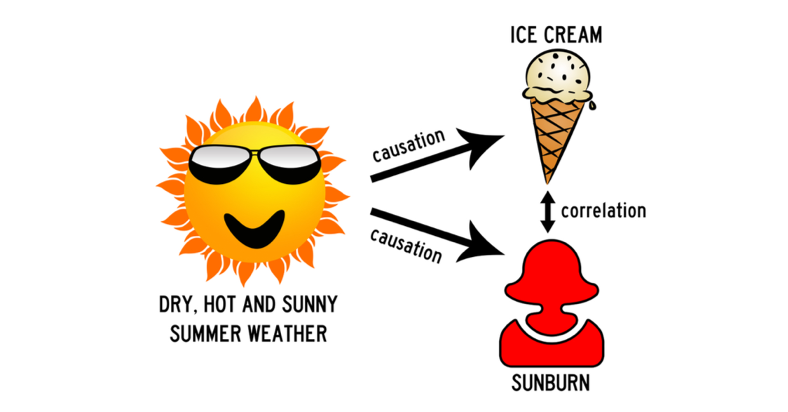

Let’s say we notice a correlation between sunburn and ice cream sales. Are people buying more ice cream after they get sunburnt? Or are people buying ice cream, then spending too long in the sun?

Perhaps, but this is insignificant compared to the true cause of the correlation. There’s a common cause for both; the sunny weather. Here, the sun is a ‘confounder’ - something which impacts both variables of interest at the same time (leading to the correlation).

So, in summary, to go from correlation to causation, we need to remove all possible confounders. If we control for all confounders (and account for random chance), and we still observe an association, we can say that there is causation.

So how can we remove confounders?

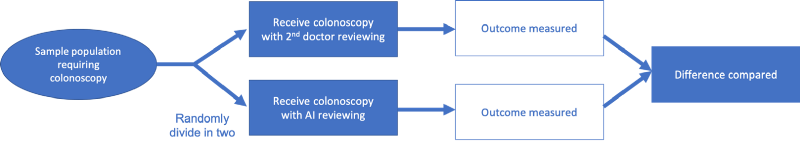

The gold-standard is the randomised control trial (RCT).

Here, we divide our sample population into two, completely randomly. One half gets one treatment and one half gets another. Because the split was (at least in theory) completely random, any differences between outcome are down to the different treatment.

|

|---|

| Source: What is the role of AI in healthcare? What the current evidence shows — Chris Lovejoy. Original paper. |

But sometimes we can’t do an RCT. Maybe we’ve already collected the data. Or maybe we’re investigating a variable we can’t change (like the impact of genetics, or the weather). What can we do?

There’s a neat mathematical approach here, called ‘stratifying on the confounders’. I won’t go into the detail here, but essentially it removes the confounders by summing up every possible combination of their values. (If interested, Judea Pearl is a pioneer in this field, and outlines the methodology here. A shorter, simpler description is shared by Ferenc Huszár here).

Causality: the future of machine learning?

Introducing causality to machine learning can make the model outputs more robust, and prevent the types of errors described earlier.

But what does this look like? How can we encode causality into a model?

The exact approach depends on the question we are trying to answer and the type of data we have available.

A recent example is this paper by Babylon Health. They used a causal machine learning model to rank likely diseases based on the symptoms, risk factors and demographics of a patient.

They trained the model to ask “if I treat this disease, which symptoms would go away?” and “if I don’t treat this disease, which symptoms would remain?”. They encoded these questions as two mathematical formulae. Using these questions brings in causality: if treating a disease causes symptoms to go away, then it’s a causal relationship.

They compared their causal model with a model that only looked at correlations and found that it performed better — particularly for rarer diseases and more complex cases.

Looking to the future

Despite the great potential of machine learning, and the associated excitement, we must not forget our core statistical principles.

We must go beyond correlation (association) to look at causation, and build this into our models.

We can do so by removing confounders; through randomized control trials, or by intelligent mathematical manipulation.

This a key step towards utilising the power of machine learning for real-world benefit without succumbing to its potential flaws.

References

(1) Machine Bias in Criminal Sentencing— Pro Publica

(2) Causal Inference in Statistics: A Primer, Chapter 3: The Effect of Interventions

(3) ML beyond Curve Fitting- inFERENCe blog

(4) From Statistics to Machine Learning — ryx,r blog

Other articles on correlation vs causation:

Appendix: The causal inference hierarchy (Judea Pearl’s Ladder of Causation)

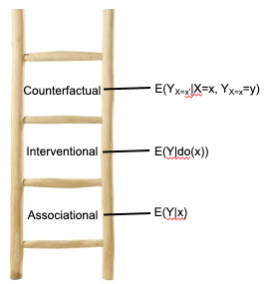

Judea Pearl describes a ladder of causal inference.

When moving beyond associational inference, he considers two main types: interventional causal inference and counterfactual causal inference.

Interventional causal inference asks “what would happen to B if I set A at value X?” If setting the value of A higher leads to a higher value of B (without confounders), we say the relationship is causal.

Counterfactual causal inference is a little trickier. We ask “Given that A was value X and this led B to equal Y, what would have happened if it A had actually been a higher value?” (ie. it asks this after the event has already happened). If A having been different would have led to a different value of B, we say the relationship is causal.

If interested in understanding these distinctions, check out the following resources:

- Causal Inference in Statistics: A Primer by Judea Pearl: A great mathematical introduction to the subject

- Book of Why by Judea Pearl: A great layman introduction to the subject, with historical and wider context

- inFERENCE blog series on causality